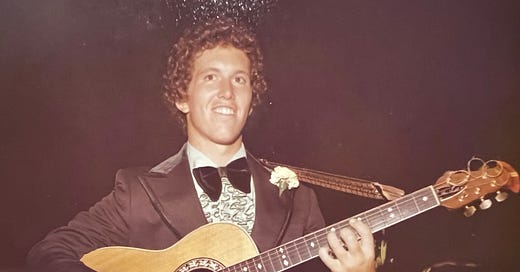

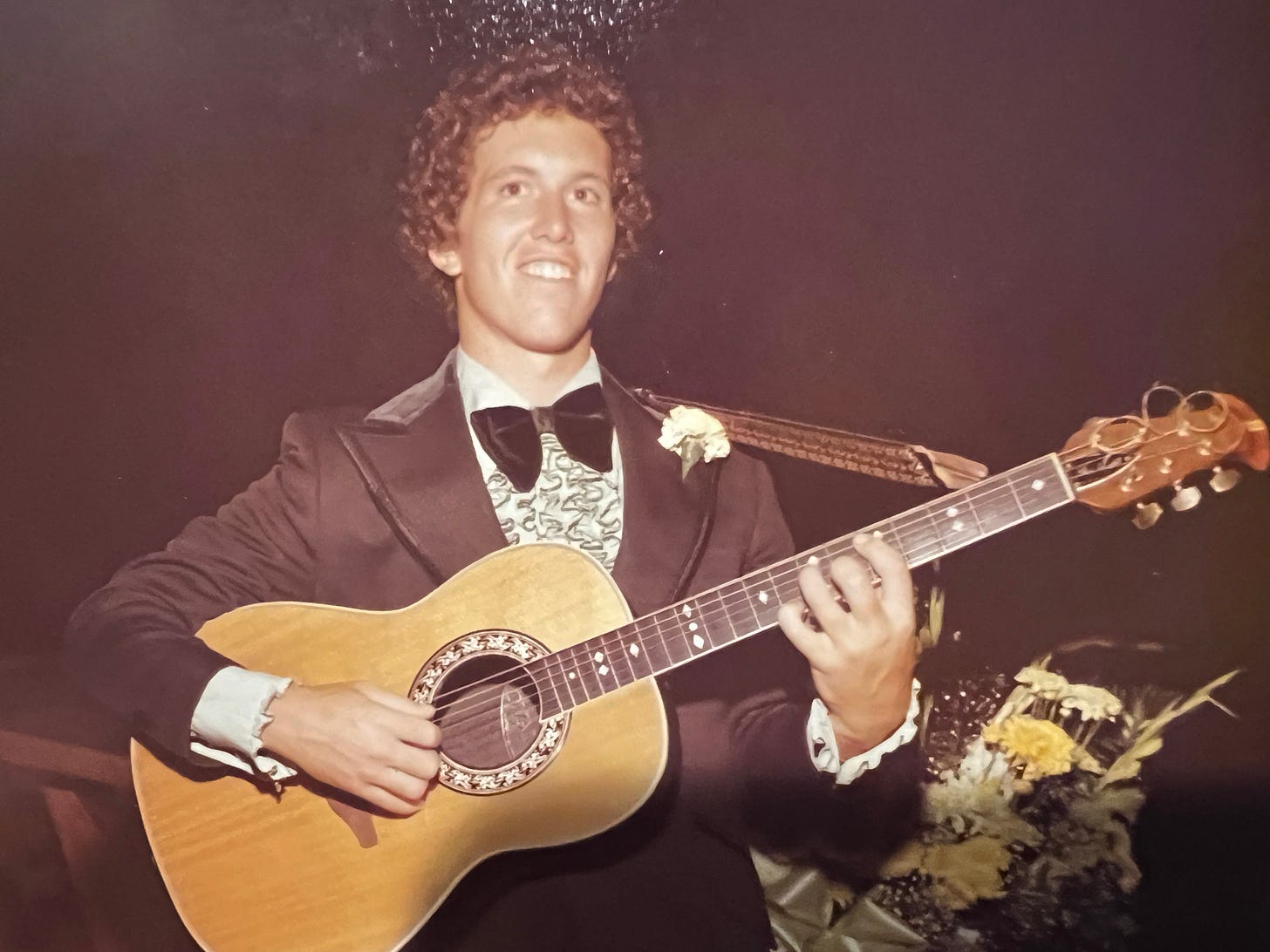

Dan Roberts at our wedding in 1975.

Editor’s note: This is the first in a two-part series related to my recent trip to Texas.

IT WAS NEARLY 50 years ago — Aug. 22, 1975 — when I gathered with my groomsmen about an hour before I was to marry Sally in Corvallis.

The room in the church teemed with pre-game nerves, ruffled shirts — sea foam green — and bow ties the size of front-door Christmas wreathes.

My stomach roiled. Danny Roberts, a guitar-playing high school buddy with whom I’d partnered to write two songs for the ceremony — melodies and singing by him, words by me — was nowhere to be seen. And he was our opening act.

Fifteen minutes later, he sauntered in, more relaxed than a sleeping cat. He was holding his guitar case, his tux sharp and his demeanor cool and collected.

“Hey, guys,” he said, sitting down to reveal bare ankles, “anyone got a pair of socks I can borrow?”

Seriously?

“OK, oh-for-one,” he said after the blank stares. “How about a guitar pick?”

Well, of course, he’d ask us that.

Among that group of young men in those malleable years of our lives—I was 21—one would become a doctor (Tom Boubel), one an overseas Nike manager (John Woodman) and one a football coach who’d win a national Division III championship at Linfield (Jay Locey).

But only one, Dan “Rodeo” Roberts, would blow across the country like a tumbleweed, driven by the disparate winds of laid-back faith and quiet desperation in pursuit of something that time would only grudgingly reveal.

As I watched him pick and play in Fort Worth, Texas, last week at the Red Steagall Cowboy Gathering, I was reminded that Danny was unlike anyone I’ve known. Reminded that pursuing a dream can be less an exercise in going from Point A to Point B than in bouncing, like a pinball, here and there until your diligence pays off, the lights flash, and the sound erupts.

Danny grew up in Pleasant Hill, east of Eugene, as the youngest of a three-brother, one-father barbershop quartet known as the Mellow D’s: Dad (Wayne), Dave, Dean and Dan. He was 5 when the group started, not much older when they claimed their highest achievement, an 11th-place finish in a Coos Bay contest. They won 75 silver dollars and on the drive home, the boys took turns plunging their hands into the pot like pirates with a chest of gold. They used it to buy their first horse.

I met Danny when I was a high school sophomore after the Roberts family moved to Corvallis, in part to give the boys a more challenging athletic experience. It worked. Dave would go on to play baseball at the University of Oregon and, in 1972, when he signed with the San Diego Padres, became major league baseball’s No.1 draft pick. Dean led our school, Corvallis High, to a 26-0 record and a state basketball title in 1970, then accepted a full ride to the UO for basketball and baseball.

Danny, a left-handed pitcher, was good but never great. He played baseball at Arizona Western Junior College in Yuma and Westmont College in Santa Barbara. He earned enough credits for a four-year degree but waited too long to do some makeup work so never officially graduated.

“Another example of me leaving stuff undone,” he later told me. “Socks. Guitar picks. You know what I mean.”

I do.

I also know how difficult it was for him to find his real passion back then. He tried out for a minor league baseball team in Gray’s Harbor, Wash., but was cut. He set chokers for a logging outfit in Oregon. He called Sally and me, trying to enlist us in a pyramid scheme involving something called “Get Off Your High Horse” shirts.

He’d show up on our doorstep in Bend after having hitchhiked from who knows where, always upbeat, always looking for the next best thing, but never too sure what that might be.

In Prescott, Ariz., while working for Pro Athletes Outreach, an organization that taught Christian principles to professional athletes, he found extra work on a ranch. Hunted mountain lions. And rediscovered his love for horses.

He went to farrier school. Began shoeing horses. Befriended a world champion bronc and bull rider who taught him how to ride the rodeo events. Competed in dozens of rodeos. And, meanwhile, kept strumming his guitar, even writing a song or two.

He bounced to Branson, Mo., worked at a Christian camp, and sang cowboy music at a pizza parlor called Shotgun Sam’s.

Along the way, he was exposed to the cowboy songs of Chris LeDoux, a bareback rider, and upstart country singer Willie Nelson. Listening to Nelson’s “Red-Headed Stranger” album was an epiphany for Dan. Watching a TV special starring songwriters who’d become famous mesmerized him. For the first time, he wondered if he could make a living writing music.

So, in 1982, at age 28, he rented a pickup truck and moved his meager belongings to Nashville. He arrived in town with $20 in his pocket, $15 of which he used to put gas in his Toyota pickup and the rest to buy a couple dozen eggs and potatoes.

He house-sat for a family he knew from church that was doing missionary work in Uganda, requiring him to take care of 70 head of cattle.

In addition, he got a construction job. While hammering atop an unfinished roof, he noticed a group of Vanderbilt women jogging past, one of whom he recognized from his days at the Missouri camp. The group regularly passed this way and his heart defaulted to words from a Kris Kristofferson/Rita Coolidge song:

I’d rather be sorry for something I’ve done

Then for something that I didn’t do …

So he asked her out. Eighteen months later, in 1987, they were married in her hometown of Tulsa, Okla. They honeymooned in Hawaii. Danny forgot his wallet.

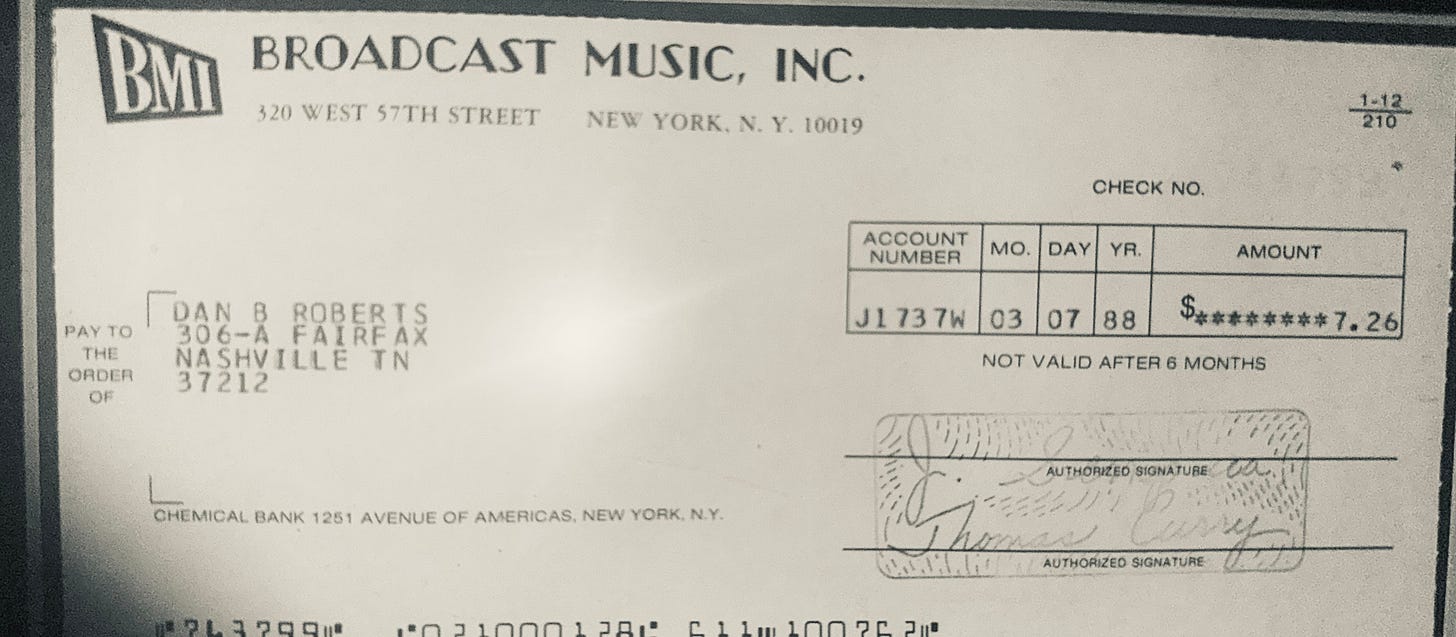

While Carol worked at Vanderbilt, Danny kept hammering on houses and shoeing horses. Meanwhile, he began selling the rights to a song here and there, his first being “Love Has a Way,” for which he was paid $7.26. The rights to his next song, “No Regrets,” were bought by Mo Bandy for $746.

Danny’ first royalty check for a song he wrote.

Danny was so pumped he packed a bag for him and Carol and picked her up after work. They blew the entire amount on an impromptu weekend in Chicago.

Back home, his quest for success continued. He wrote a lighthearted song called “Hand-Me-Downs” about his poverty, one stanza of which went like this:

Everything seemed to be going swell

Was eatin’ most my meals at the Taco Bell

What more could one man want than to just get full?

But after a while as you may guess

The burritos and the beans made quite a mess

They didn’t look good on my multi-colored hand-me-downs.

Even as he made light of his plight, Danny was disappointed deep inside.

“I didn’t move to Nashville to shoe horses and do construction,” he says.

Carol floated a plan: have Dan spend a full year writing songs and if nothing substantial “took” he’d move to another career pursuit.

It didn’t take much convincing. Dan and writing partner Bryan Kennedy began kicking out songs and cutting demos, knowing that the presentation was critical. They scraped together enough money to hire a handful of studio musicians, including a kid they’d heard at the Bluebird Café who wasn’t half bad.

His name was Garth Brooks. They paid him $75 to help record one song.

“He didn’t have a record deal at that point,” Danny remembers. “He was working two jobs: sweeping out a church and selling footwear at a boots store.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Bob Welch: Heart, Humor & Hope to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.